MCO’s Bach: Spirit & Spectacle can be heard in Melbourne on Sunday 19 June at Melbourne Recital Centre & Friday 24 June at The Deakin Edge, Federation Square.

BACH: SPIRIT & SPECTACLE

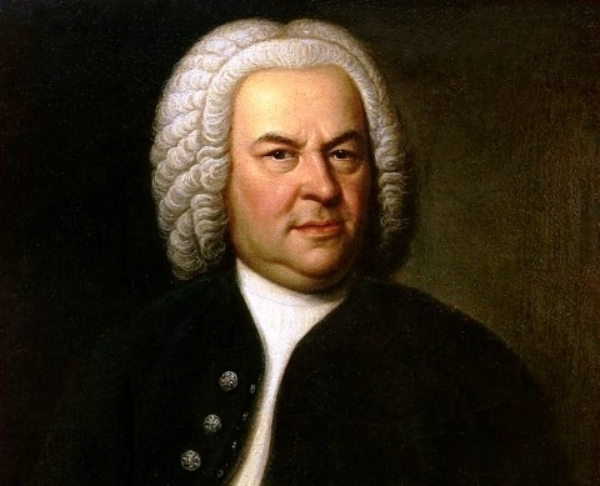

It is difficult to capture the sheer magnitude of the influence of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) on Western music. This German composer was an all-round musician and teacher whose life was centred around his family, work and his God.

He took the forms and techniques of his time and extended, expanded and enhanced them so that future generations would continue to explore his inventive mastery and achievement. At whatever time we listen to his music we are continually presented with the opportunity to consider perspectives both from our past and present. He offers a medium to consider our time in relation to his in the eighteenth century.

Bach/Stokowski

Mein Jesu, was vor Seelenweh BWV487 (arr. string orchestra)

Mein Jesu, was vor Seelenweh (My Jesus! Oh what anguish), written for voice and continuo, is one of the sixty-nine works in G. C. Schemelli’s Musicalisches Gesang-Buch (Song Book) published in 1736. The work is in two sections each conveying the anguish of the original text.

Leopold Stokowski (1882–1977) was one of the great conductors of the 20th century. He is remembered not only for his many recordings but particularly for his association with the Philadelphia Orchestra and for appearing in Disney’s film Fantasia (1940). Stokowski was renowned for his renderings, arrangements, orchestrations and transcriptions of repertoire. In these works he provided insights from an original medium to the orchestra.

Johann Sebastian Bach

Brandenburg Concerto No 3 BWV 1048

I. [no tempo indication] (Allegro)

II. Largo (Siciliano from Violin Sonata BWV 1017)

III. Allegro

The six concerti grossi known as the Brandenburg Concerti were written between 1711 and 1720 and dedicated to Christian Ludwig, Margrave of Brandenburg, in March 1721. The instrumentation of each concerto is different, suggesting that the works were not intended to be performed as a set but individually according to the availability of the required musicians.

The works in the collection are significant for their unusual combinations of instruments and textures, with the third and sixth concerti being for strings only. The third concerto is scored for three violins, three violas, three cellos and continuo.

The three movements provide great contrast of thought and intent. The outer movements are in the ritornello form with regular returns to the main idea and contrasting sections. In the score, the second movement consists merely of two chords. In contemporary practice, a movement of another Bach work is sometimes inserted at this point, as in today’s performance. In this work, listen for the delightful, overlapping interplay between the three violins, violas and cellos.

The Art of Fugue BWV 1080: Contrapunctus V

Die Kunst der Fuge (The Art of Fugue) is an unfinished work by Bach composed over the last decade of his life. The name contrapunctus is given to each of the fugues in the collection. The work is an exploration of contrapuntal possibilities of a single musical subject and is considered to be the culmination of Bach’s contrapuntal experiments. It is not entirely clear what instrument or combination of instruments Bach intended to perform the work. It has been especially performed by keyboardists and string quartets.

Contrapunctus V is an example of a stretto fugue where the entries of the subject (or main idea) are not sequential but are overlapping. In this fugue, the the theme appears both in its regular and an inverted form, meaning that the upward movements in the line of the regular theme become downward movements and vice versa.

Calvin Bowman

Die Linien des Lebens

Calvin Bowman writes: ‘Die Linien des Lebens’ is a cycle of seven songs set to the poetry of Friedrich Hölderlin (1770-1843). It was largely written during a period as Artist in Residence at Montsalvat in 2010.

Hölderlin was a German Romantic poet. As such, I have created settings which endeavour to suit the poetry’s romantic outlook. The poems I’ve selected reveal, in particular, Hölderlin’s love of nature. Furthermore, there is always a melancholic tinge to his poetry which I find to be most appealing.

Whilst perusing poems for possible inclusion in the cycle I came across a goodly number of beautiful fragments of poetry which Hölderlin failed to craft into complete poems. These I have accompanied with pizzicati strings to signify their incomplete states. Furthermore, the settings of these fragments attempt to hint at the madness into which Hölderlin descended at an all too young age.

Ernst Zimmer, a carpenter, and his family cared for Hölderlin for nearly four decades after his mental demise. The title of this cycle, ‘Die Linien des Lebens’, comes from the first line of the final poem in the set, ‘An Zimmern’. Aptly, this gift for Hölderlin’s saviour was written on a piece of wood.

J. S. Bach

Cantata BWV 115: Bete aber auch dabei

Bete aber auch dabei (But you should also pray) is an aria from Cantata BWV 115 Mache dich, mein Geist, bereit (Make yourself ready, my spirit) written for the 22nd Sunday after Trinity. The work was composed in 1724. The soprano aria is a gentle interplay between the voice, instrumentalists and continuo.

Mass in B minor BWV 232: Laudamus te

The Mass in B minor is one of Bach’s crowning achievements. This setting of the Latin mass was completed between 1748 and 1749. Laudamus te (We praise you) is the second movement of the Gloria. This exuberant exclamation of praise is scored for soprano, solo violin, strings and continuo.

Cantata BWV197: Vergnügen und Lust

The dance-like aria Vergnügen und Lust (Pleasure and joy) is found in the cantata Ehre sei Gott in der Höhe (Glory be to God in the Highest), written by Bach for Christmas in 1728. He revised it in 1736–37 as the wedding cantata Gott ist unsre Zuversicht (God is our confidence).

Violin Concerto in D minor BWV1052R

I. Allegro

II. Adagio

III. Allegro

Based on what is known from Bach’s contractual composing obligations and his correspondence, scholars assume that a fairly large part of Bach’s compositional output has been lost. The harpsichord concerti of Bach have been identified, through stylistic analysis, to be transcriptions of earlier, now lost, works by Bach for other instruments. In the case of this concerto in D minor, the range of the melodic material and style of patternwork strongly suggest it originates from a lost Bach concerto for violin. As such, it was reconstructed in the early twentieth century by Robert Reitz. The sheer momentum of the outer movements is contrasted to the pensive aria-like slow movement.

*David Forrest & Richard Jackson