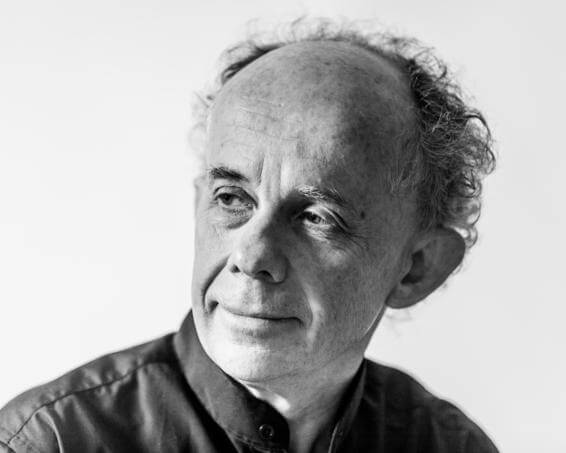

Our Artistic Director, William Hennessy, took some time out from his schedule to provide some reflections on MCO’s first program for 2015, Mozart in Prague.

The cellos and basses soar alone together, deeply and nobly. Evoking eternity, this Dvorak melody could have come from the Middle Ages. (Perhaps it did?) The possibilities for what may follow seem limitless. Will there be tragedy? Will there be joy?

The concert has begun!

The violins then respond to the message sent from their lower relatives. Whilst at first remaining reflective they nevertheless begin to show that there will be hope and tenderness. Not despair… And then it is time to dance. A restrained yet inwardly ecstatic dance with the kind of joy that brings tears, tears of wonderment, tears of the affirmation of what is beautiful in our humanity and what is beautiful beyond it.

What follows on this occasion is the grandest opening of all the twenty-seven piano concertos of Mozart.

This concerto (no 25) is actually much more suited to the title of “Coronation Concerto” than the Coronation Concerto (no 26) itself, the latter having been subtitled under false pretense by Mozart’s publisher with the writing of the actual “Coronation Concerto” having nothing whatsoever to do with the coronation which was going on at the time! What’s more, the atmosphere of the opening of the “Coronation Concerto” is subdued and furtive, whereas in this 25th Concerto I have always imagined a scene which was nothing less grand than the crowning of an emperor, opening of an Olympic Games or celebration of a great collective human triumph, (though certainly not the knighting of a duke!)

So for me, this is the real Coronation Concerto, regardless of what anyone else says or thinks! It also contains one of my favourite moments in all music (about four minutes into the last movement). At that point, in a fit of sheer spontaneity, the piano introduces a brand new tune. I always imagined here that the sopranos (on this occasion the piano which then hands the responsibility to the oboe) are the voice of the angels, but the cello and bass are somehow collectively the voice of God. The effect here of the combined cellos and basses is every bit as moving in it’s own way as the Dvorak “Middle Ages” music which the same combination gave us at the opening of the concert.

This is how I have always understood music. Not so much in terms of chords and keys and crotchets and quavers, but in terms of story telling and creation of atmosphere with direct connection to that which we feel most deeply about. (My father couldn’t read or understand crotchets and quavers at all, but he certainly understood music and knew how to listen to it and how to play it.)

After interval, Dvorak’s son in law, Josef Suk, will take us to a related magical world to that of his father in law’s. It is a gem so exquisite that it removes any doubt I could ever have had about the very existence of magic. We will be careful not to disturb it.

There’s plenty of magic too in Mozart’s Prague Symphony, which he completed on the 6th December 1786, two days after he completed the twenty-fifth concerto. The magic however in the symphony is more often than not that of high drama and high energy. There is a kind of athletic thrust to this music, especially in the last movement where leaps, cascades, darting, diving and even a sense of jousting and boxing abound. It’s wonderful, muscular, earthy stuff!

In the first two movements of this three movement symphony we often journey to darker places; places of ambiguity, strange places with suggestion of strange forms and emotional uncertainty relieved by occasional bursts of light, radiance and reassurance.

The Prague Symphony is in many ways the beginning of what became the great romantic symphony of the nineteenth century where private, personal statement and even bombast at times tested the boundaries of structure and aesthetics. I feel Mozart himself weighed into this discussion in some way when he wrote about the nature of extremeness in music. “ No matter how extreme the emotion, music must always remain music. Music must always delight the ear,” something he achieves most handsomely in this audacious work which concludes our concert.